Every year around this time, Dan and I provide an update on contribution limits for retirement savings accounts. And every time we say something along the lines of “Put time on your side, and sock away as much as you can as early as you can.”

Well, this year is no different.

A key tenet of our approach is to spend time in the market. I can’t think of a better place to do that than in a retirement account. First, you are incentivized to think long-term as there are penalties if you withdraw your money early. And, more importantly, your money compounds unimpeded by taxes. That’s powerful.

It’s why Dan continues to fund his retirement accounts to the full limit of the law even though he’s getting closer and closer to retirement age. And I’ve been funding my accounts since I first graduated from college—future retirement-age Jeff will thank younger Jeff some years down the road.

I know many of you have already retired and are more worried about taking your required minimum distribution (RMD) each year than contributing to a retirement account. I’ll be covering RMDs in the future, but even for those in retirement I think you’ll find some value in reading on.

First, maybe you have a younger person in your life who could benefit from hearing this—by all means, please share my thoughts and advice. Second, as of 2020 there is no age limit when it comes to contributing to a traditional or a Roth IRA. So, even if you are of retirement age, but are earning some income, you can and may want to contribute to a Roth IRA as part of a plan to pass your wealth on to the next generation.

Before getting to the details of 2023’s contribution limits, I want to spend a little time presenting some of the evidence behind my advice to save and invest early and often. I want to cover a few different angles so let’s dig in.

In all of the analysis that follows, I’m starting my calculations in 1986 which is when the maximum amount an individual could contribute to a 401(k) dropped from $30,000 (yes, $30,000!) to $7,000. Why? Well, it just seems like a more reasonable amount to expect someone might have maxed out at back in 1986 when the average salary, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was around $18,600. I’ve then run each scenario with updated 401(k) contribution limits each year since then. Finally, to keep it simple, I’m using 500 Index (VFIAX) as my stock market investment vehicle.

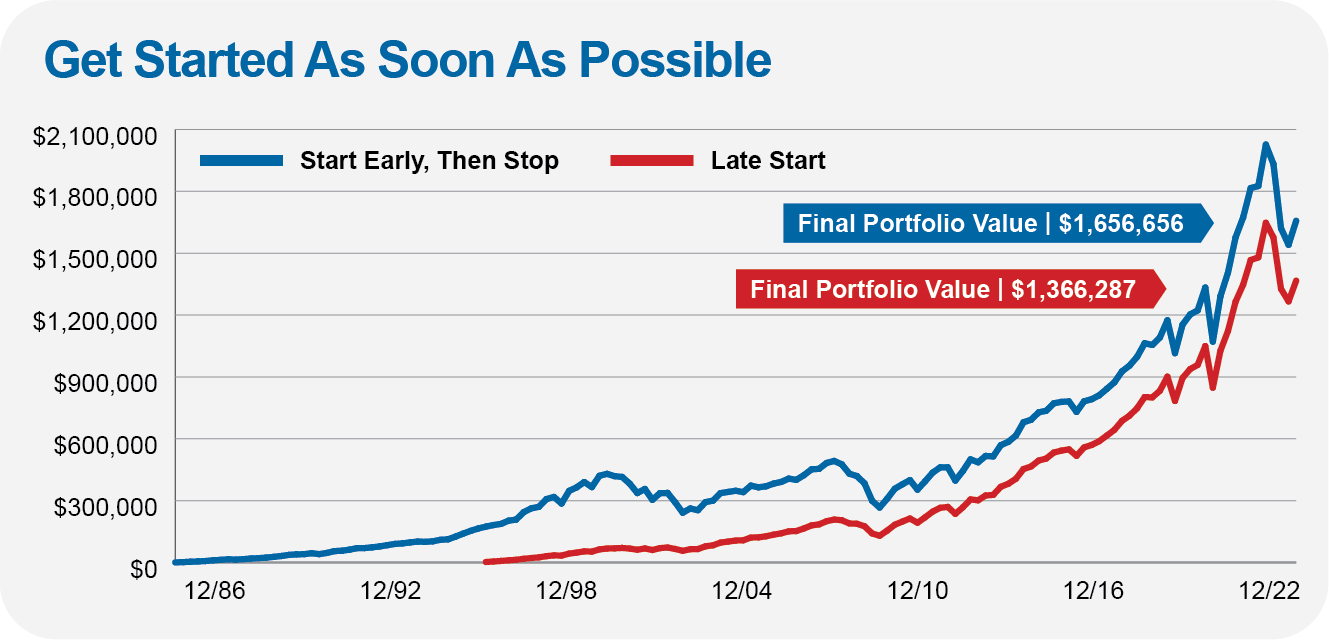

First, let’s look at the importance of starting early in one’s career by comparing two savers—an early starter who also stops early versus a late starter who contributes for longer.

Our early bird contributes the max to their 401(k) for the first 10 years of their career, and then stops. To be specific, from January 1986 through December 1995, they spread their contributions evenly throughout the year so that they maxed out every year—automatically invested in 500 Index each month. After December 1995, they never touched their 401(k) again—never contributed another penny and left the money where it was, in the stock market. All in, our early starter socked away a little over $80,000 in their 401(k).

Our late starter didn’t contribute to their 401(k) for the first decade—only getting in on the action in January 1996. At that point, they picked up where our early starter left off—contributing to 500 Index each month so that they too maxed out for the year. Through the end of 2022, our late starter has contributed a little over $400,000 to their 401(k).

You know what my next question is, right? Who do you think is ahead after 37 years? Incredibly, the early bird didn’t get the worm, she got the gold ring.

Yes, even though our early starter hasn’t contributed to her account for decades and contributed far less overall, her portfolio is nearly $300,000 larger today—$1,656,656 for the early starter versus $1,366,287 for the late stater.

That’s the power of starting early and spending time in the market. That headstart and extra ten years really paid off.

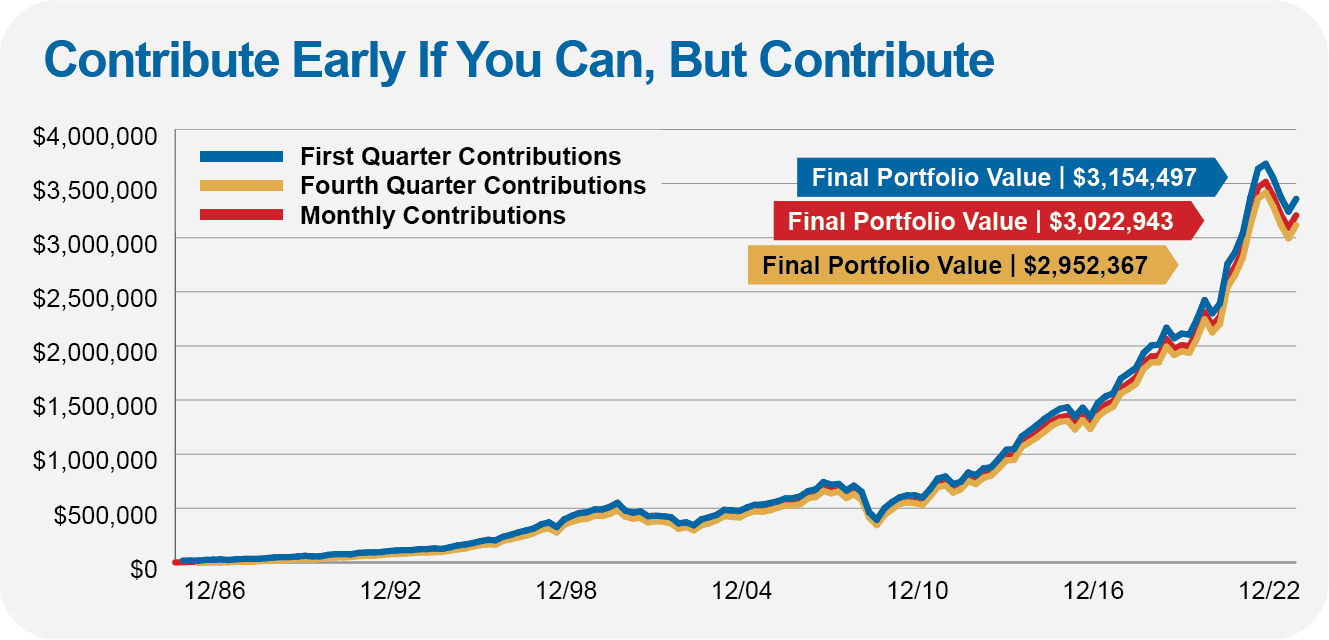

Another point: When Dan and I advise people to “save early,” we also mean that you should consider front-loading your contributions each year. If you can raise your contribution amount and max out early in the year, the earlier the better, do it.

Important caveat: Check how your company matches your contributions. If it does so by pay period rather than on an annual basis, then you won’t want to sock all your money away up-front, as you might miss the biweekly or monthly matches. Speak with your benefits manager to make sure you don’t miss out.

Our advice to contribute early in the year is based on the assumption that markets rise more often than they fall—hence our preference to buy early at what could be the lowest prices of the year.

That sounds great but I wanted to put that assumption to the test, so I compared three savers. One investor made all their contributions in the first three months of the year. The second saver waited until the final three months to make their contributions. And our third participant made consistent monthly contributions. All three investors maxed out their contributions each year and held only 500 Index.

As you can see in the chart below, after more than three decades the differences in approach haven’t led to huge differences in results. All three investors have roughly twice as much in their 401(k)’s as the two investors we looked at before who either started early but stopped or got a late start.

That said, the investor who was able to contribute early in the year, is ahead of the other two by around $130,00 to $200,000. It’s a difference of 4% to 7% of the portfolio. Is that make or break for these investors? No. But if you can swing it, why not put the odds in your favor?

Your main take-away, regardless of how early you can max out your contributions, should be to “just do it”—contribute, invest and stay in the market.

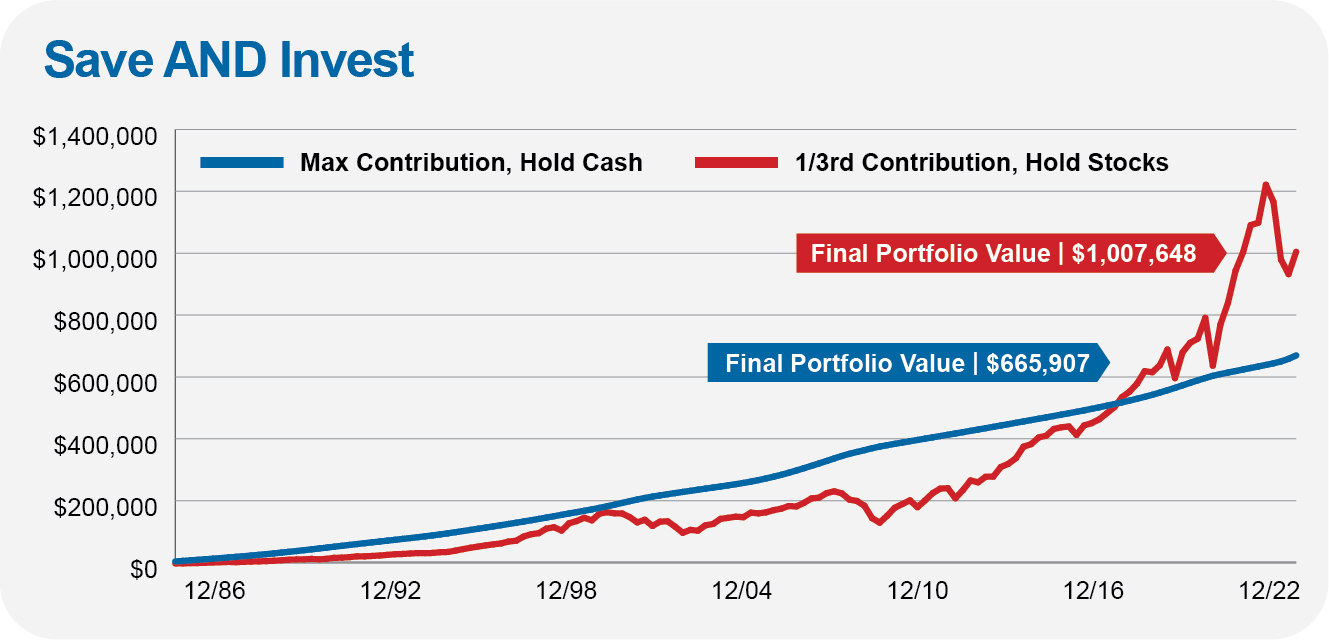

Finally—and I can’t stress this enough—you need to save and invest. Think of savings as the fuel you put in your car. You need gas in your car to go, but if you don’t turn the engine on, you won’t get very far. Investing your money in the market is like turning the key and stepping on the gas.

Again, let’s compare two savers. One saver was able to sock away the maximum amount in their 401(k) every year since 1986. They’ve contributed nearly $500,000 to their 401(k) over 37 years … but held cash the entire time. I’ll use Cash Reserves Federal Money Market (VMRXX) as my cash account. The second saver wasn’t able to put away as much—only contributing a third of the max allowed each year or about $160,000 in total—but they invested their contributions into 500 Index rather than letting it lie fallow in a money market.

Who do you think is ahead? You probably guessed it by now, but, yes, even though our second saver put away far less money, they are well ahead thanks to the power of compounding. It took about three decades for them to catch up to their higher-savings rate friend, but today their account is 50% larger and there’s really no way for our cash investor to catch-up. Even if the current bear market has another leg lower, the stock investor is poised to leave their cash-holding friend in the dust.

You simply can’t save your way to riches. You have to invest. Our conservative saver with nearly $666,000 in the money market isn’t in dire straights … but had they invested that money in the stock market instead of sitting in cash, they’d have about $3 million dollars in their 401(k). That’s a very different proposition.

I should also add that you shouldn’t count on superior investment returns to bail out a low savings rate. It’s really the intersection of the two—a robust savings rate and investing—that allows you to harness the power of compounding.

One final question to address: How much is enough? How much do you really need for retirement? Unfortunately, there’s no one answer—it’s going to depend on your individual situation.

A while back Fidelity offered a guideline for retirement savings suggesting that by the time you are 67, you should have socked away eight times your annual income. This will give you a shot at having 85% of your pre-retirement annual income available to you after you retire. So, if you’re earning $65,000 per year at age 67, you should hope to have at least $520,000 put away.

While I can’t vouch for Fidelity’s math, I do agree with the underlying message: When it comes to your retirement, the more you can save and invest, the better off you will be.

Savings Limits Rise

Now to the good stuff—how much you can sock away in tax-deferred accounts where the power of tax-free compounding can really make your money grow. Believe it or not, a silver lining of last year’s high inflation rate is that the limits imposed by the IRS on our retirement savings rose by 8% to 11% for 2023. That translates to an additional $5,000 if you are in a position to contribute to a SEP IRA, an additional $2,000 in your 401(k), another $1,500 in a SIMPLE IRA and $500 more in a regular IRA.

I’ll be taking the IRS up on their “offer” to boost my retirement contributions in 2023. As I said, I’m a big believer in retirement savings plans. I have been fortunate enough to be able to contribute the max in years past and plan to keep doing so. And yes, when I can, I add my retirement money early in the year—I also do this with “other” vehicles, like my son’s 529 plan.

Of course, there will be years like 2022, when buying early meant buying at the highest prices of the year. Okay, I’ll take that lump, because I know that we simply can’t predict how the markets will fare in any given month or year. But remember, I showed you that buying early works out in your favor over time. Let’s put it this way: I contributed to my son’s 529 plan on January 4, 2022—the day after the market’s peak—ouch. That didn’t stop me from making this year’s contribution on January 4th, again.

Coming back to retirement plans, you can find the contribution limits for 2022 and 2023 in the table below. I include 2022 limits so you can see the change but also—and more importantly—because if you haven’t put the max in for 2022, you have until April 18, 2023, to do so.

Contribution Limits for Retirement Savings Accounts

| 2022 | 2023 | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IRA | $6,000 | $6,500 | Indexed to inflation |

| SIMPLE IRA | $14,000 | $15,500 | Indexed to inflation |

| SEP IRA* | $61,000 | $66,000 | Up to 25% of comp. |

| 401(k), 403(b) & 457(b) plans | $20,500 | $22,500 | Indexed to inflation |

| *Contribution is the lesser of the percentage allowed or the limits as stated. Check with your accountant for the specifics of your individual situation. | |||

Catching Up

As if the opportunity to invest hard-earned dollars for retirement, tax-deferred, wasn’t good enough news, the fact that folks like Dan, age 50 and older, can save additional dollars is a bonus.

If you’re past the half-century mark, you can once again contribute an extra $1,000 to your IRAs in 2023 for a total of $7,500. The numbers are even higher for other retirement plans (see the table below). If you are over 50 or are turning 50 in 2023, take advantage of this option. And if you didn’t do so in 2022, you still have until April 18, 2023, to make the most of this fantastic feature.

If you’re newly eligible for the catch-up contributions, talk to your company’s human resources or employee benefits department about your in-house retirement account, and make sure that they’ll accommodate you. While employers are not required to allow the catch-up contributions, most have gotten with the program by now.

Catch-Up Limits

| 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|

| IRA | $1,000 | $1,000 |

| SIMPLE IRA | $3,000 | $3,500 |

| 401(k), 403(b) & 457(b) plans | $6,500 | $7,500 |

Regardless of your age or income level, you should strongly consider making your 2023 contributions now, rather than later. But, if you still haven’t done all you can for 2022, do that first, before the opportunity to contribute ends in April. Retirement accounts are great long-term savings and investment vehicles, and regular contributions, when properly invested in, say, one of our Portfolios, will really add up over time.

I’ve got a (very) long way to go, but I’ve been walking this talk for nearly two decades and am very, very happy with the results.