Real estate (or land) is one of the oldest assets. For many of us, our homes are the largest assets on our balance sheets. And though it is a major investment for many consumers, real estate doesn’t always get the same attention from investors. Real estate accounts for just 3% of Total Stock Market Index’s (VTSAX) portfolio, so one could say it’s an afterthought for investors but front-of-mind for consumers.

I often lump Real Estate Index (VGSLX) into my sector fund coverage. But I’ll argue today that real estate is less a sector of the stock market and more a hybrid asset class that we should view independently.

Right now, I’m also seeing many dire headlines about real estate from an investment perspective. For example, The Debt Crisis Looming in Commercial Real Estate or A Real-Estate Haven Turns Perilous With Roughly $1 Trillion Coming Due. And, of course, higher mortgage rates have impacted the housing market. The fearmongering machine is up and running full steam.

So now is an opportune time to roll up our sleeves and take a hard look at the basics of real estate—particularly from the perspective of an investor rather than a homeowner.

Key Points

- Your home is not an investment.

- Real Estate Index’s return is driven by income, not rising property prices.

- Real estate returns have been attractive, but the risks have been outsized.

- You can diversify a portfolio by adding Real Estate Index, but it’s not a must-own.

Your Home or an Investment?

To be clear: The home you live in is not an investment in the traditional sense. You live in your house—you are consuming it. For most of us, our abode doesn’t generate any income.

While some people will tell you that their house has been a terrific investment, I’m skeptical. Most homeowners neglect to factor in all the costs—mortgage interest, insurance, taxes, repairs and maintenance, and so on—when calculating the “return” on their investment. I’ll acknowledge that some folks have made good returns on their homes, but that shouldn’t be your expectation.

Buying real estate for investment purposes is a different proposition. Yes, you’ll incur similar costs as with a home, but in this case, you are looking to generate income from your property—typically by renting it out.

In some cases, you may expect the property to rise in price. For example, say you are buying in an up-and-coming location. Or you could purchase a fixer-upper and make a return by sprucing it up and flipping it.

But, again, for most properties, the return comes from the income you earn. That’s physical property.

Keeping Our House in Order

In this article, I am not going to try to answer the question of whether you should pay off your mortgage (a good question for another day). Instead, I will approach real estate investing as a long-term proposition.

That means I will focus on the publicly traded real estate you and I can buy via Vanguard’s mutual funds and ETFs. Yes, fund companies are finding ways to make private real estate increasingly accessible. But my general advice is to steer clear of all private REITs. I can think of a few exceptions, but if you go down that road, you are introducing higher fees, less liquidity, less-transparent pricing and a host of other issues into the equation. You probably don’t need it.

Plus, Vanguard has yet to dip its toes into a private real estate product, so we can set it aside for another day. I will also put Global ex-U.S. Real Estate Index (VGRLX) aside—let’s discuss whether adding real estate generally makes sense before asking if we want some of our real estate holdings overseas.

What Are REITs?

As any first-time home buyer can tell you, you need money to buy property. And buying a diversified portfolio of properties takes, well, even more money. It’s not something most of us can afford—even if we were then capable of managing multiple properties. This is where REITs—real estate investment trusts—come into play.

Think of a REIT as a mutual fund. The managers of a REIT pool capital from multiple investors and then purchase (and manage) multiple properties. REITs give small investors instant diversification and access to professional management. And like mutual funds, REITs come in different flavors—some are very diversified, while others focus on specific types of properties (think offices or warehouses or apartment buildings or shopping centers).

The mutual fund analogy isn’t perfect, though. REITs trade like a stock throughout the day. REITs are also taxed differently and must pass along at least 90% of their income each year to their investors. Still, the core idea of pooling capital to achieve immediate diversification and professional management is the same.

Put a bunch of REITs together into a fund, say, Real Estate Index, and you can achieve a level of diversification that we mere mortals could never achieve on our own. By holding 165 REITs, Real Estate Index owns thousands of properties of all shapes and sizes nationwide. The table below shows the property types in Real Estate Index’s portfolio.

Different Property Types

| Sector | Weight |

| Industrial | 16% |

| Telecom Tower | 13% |

| Retail | 12% |

| Multi-Family Residential | 9% |

| Data Center | 8% |

| Health Care | 8% |

| Self-Storage | 7% |

| Other Specialized | 6% |

| Single-Family Residential | 5% |

| Office | 4% |

| Real Estate Services | 4% |

| Hotel & Resort | 3% |

| Timber | 3% |

| Diversified | 2% |

| Other | 1% |

| As of 6/30/2023. Source: Vanguard and the IVA. | |

The Theory

Real estate (and, by extension, REITs) is, in many ways, a hybrid asset. Most of the returns they generate come from income, like bonds. However, like stocks, the price of the properties is driven by the market—there is no guarantee of what price you will receive when it comes time to sell. Real estate is also a real asset (it’s in the name), so we should expect prices to rise with inflation.

Given its hybrid nature, real estate should land between stocks and bonds when it comes to risk. And in the context of a diversified portfolio, real estate should complement traditional stock and bond holdings.

Income, Income, Income

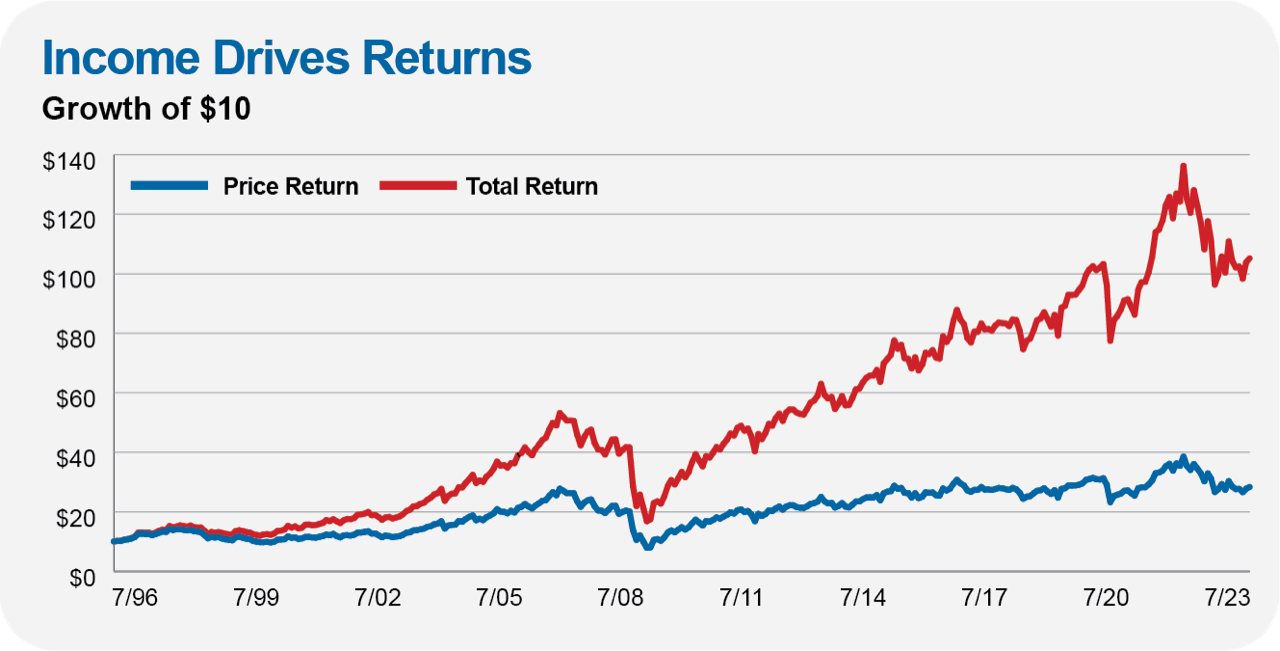

Let’s examine my contention that income drives real estate returns. This is a relatively easy one to confirm.

Since its 1996 inception, Real Estate Index’s net asset value (price) is up 181%. To be clear, that’s the price return, not counting income. An investor who reinvested the fund’s distributions is up 952% over the same period. In other words, income (and the reinvestment of that income) accounted for 80% of the fund’s total return.

While considering the fund’s price return, let’s bring inflation into the equation. Have real estate prices risen with or beaten inflation?