Spending time in the market—harnessing the power of compounding—is how most people should approach growing their wealth.

Unfortunately, it’s a message and approach that doesn’t resonate in today’s age of instant gratification. It’s not flashy. It’s also not going to make you rich quickly. (If you want to get rich quickly, you have to be willing to get poor quickly, as well.)

Building wealth means being disciplined. It involves saving (deferring consumption, living below your means, whatever you want to call it), investing, and patience. Like planting a tree, it takes time to see the results.

I’ve written about compounding before, but as I recently provided Premium Members with an update on 2024’s retirement contribution limits, I have the topic on my mind again.

I appreciate that young workers may be skeptical about contributing to a 401(k) or IRA, but the best time to start building your nest egg is now, not later. And if you no longer consider yourself a “young earner” and are only beginning to save and invest now, don’t kick yourself too hard—you can’t change the past. What matters today is that you get started and stick to your plan.

So, here’s some evidence behind my advice to save and invest early and often. I’ll cover it from a few different angles. Feel free to share this article if you know anyone who could benefit from this message.

Methodology

In all of the following analysis, I’m starting my calculations in 1986, when the maximum amount an individual could contribute to a 401(k) dropped from $30,000 (yes, $30,000!) to $7,000.

This seems like a more reasonable amount to expect someone to have maxed out in 1986, when the average salary, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, was around $18,600. I’ve run each scenario with updated 401(k) contribution limits each year since then.

And while I’m using 401(k) contribution limits to try and make my examples as realistic as possible, don’t get too caught up in the 401(k) details—this is about saving and investing early.

Finally, I’m using 500 Index (VFIAX) as my stock market investment vehicle to keep it simple.

Start Early

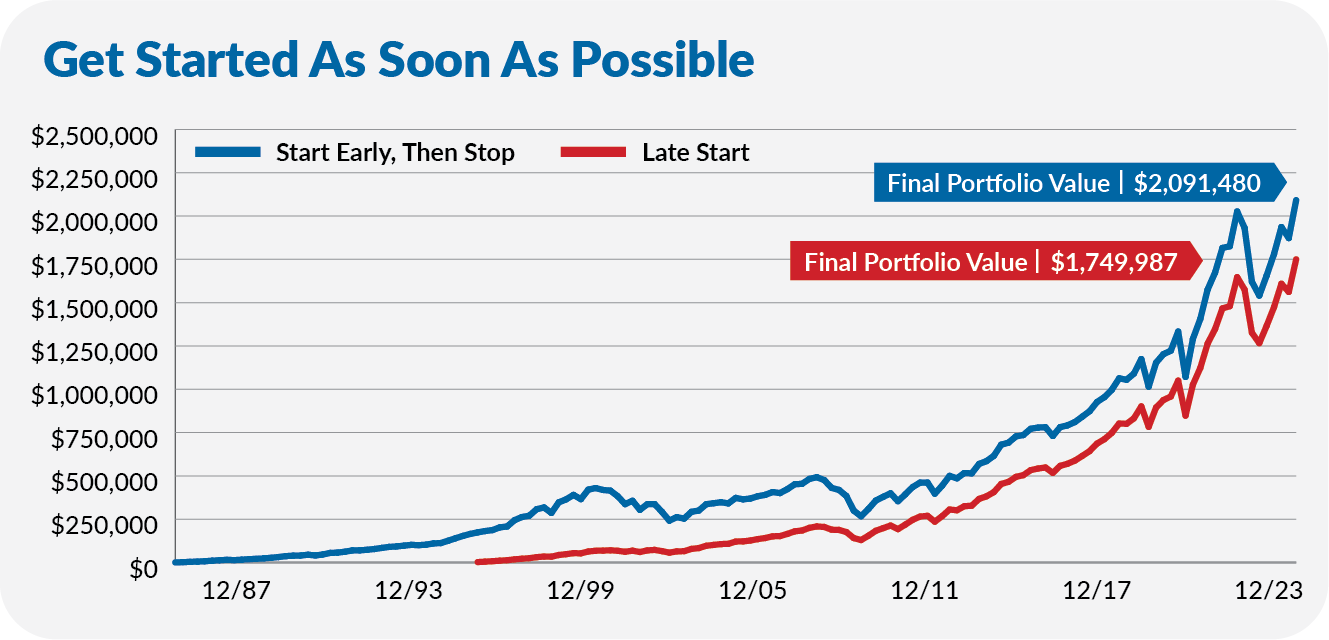

First, let’s look at the importance of starting early in one’s career by comparing two savers—an early starter who contributes and then stops early versus a late starter who contributes for longer.

Our early bird contributes the maximum to her 401(k) for the first ten years of her career and then stops. To be specific, from January 1986 through December 1995, she spread her contributions evenly throughout the year so that they maxed out every year—automatically investing in 500 Index each month.

After December 1995, she never touched her 401(k) again—never contributed another penny and left the money where it was, in the stock market, automatically reinvesting distributions. All in, our early starter socked away a little over $80,000 in her 401(k).

Our late starter didn’t contribute to his 401(k) for the first decade—only getting in on the action in January 1996. At that point, he picked up where our early starter left off—contributing to 500 Index each month so that he, too, maxed out for the year. Through the end of 2023, our late starter has contributed a little over $430,000 to his 401(k).

You know what my next question is, right? Who do you think is ahead after 38 years? Incredibly, the early bird didn’t get the worm; she got the gold ring.

Yes, even though our early starter hasn’t contributed to her account for decades and contributed far less overall, her portfolio is $340,000 larger today—$2.09 million for the early starter versus $1.75 million for the late starter.

That’s the power of starting early and spending time in the market. That head start and extra ten years really paid off.

Save & Invest

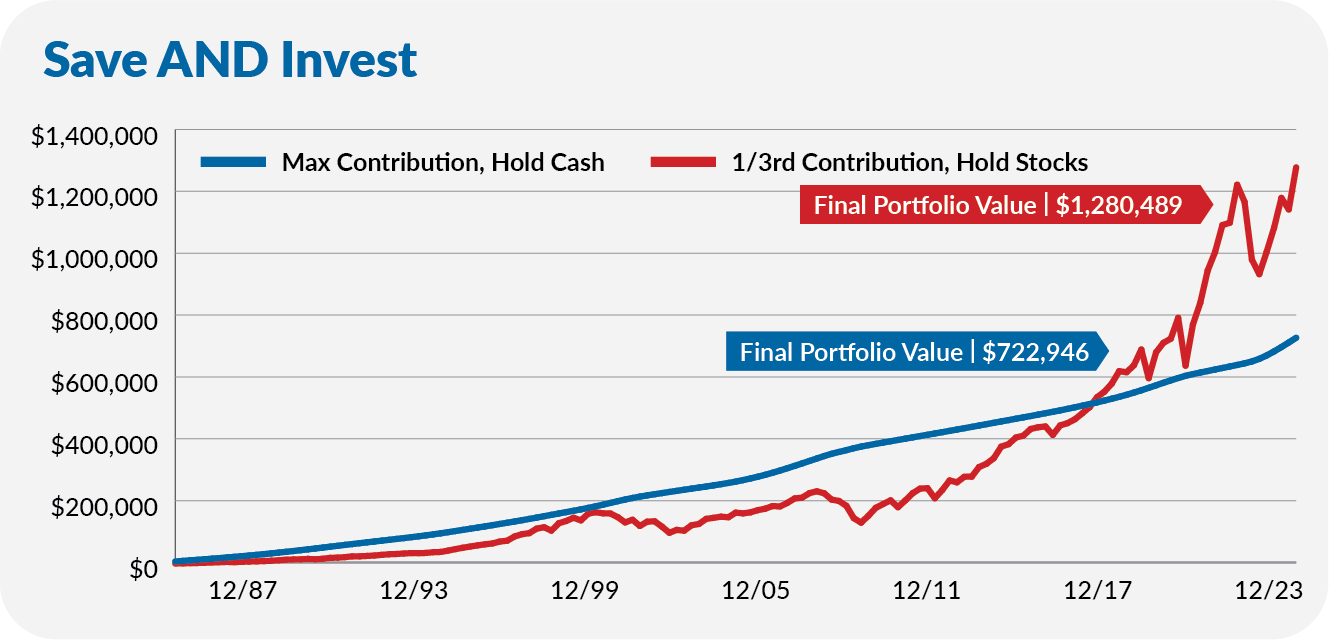

I can’t stress this enough—you need to save and invest. Think of savings as the fuel you put in your car. You need gas in your car to go, but you won’t get very far if you don’t start the engine. Investing your money in the market is like turning the key and stepping on the gas.

Again, let’s compare two savers. One saver socked away the maximum amount in her 401(k) every year since 1986. She contributed around $510,000 to her 401(k) over 38 years … but held cash the entire time. I’ll use Cash Reserves Federal Money Market’s (VMRXX) returns to represent the cash account.

The second saver couldn’t put away as much—only contributing a third of the max allowed each year, or about $170,000 in total—but he invested his contributions in 500 Index rather than letting it lie fallow in a money market.

Who do you think is ahead? You probably guessed it by now, but even though our second saver put away far less money, he ends up well ahead thanks to the power of compounding.

It took about three decades for our investor to catch up to the saver, but today, his account is 75% larger, and there’s no way for our cash investor to catch up. Even if a bear market temporarily levels the playing field, the stock investor will leave their cash-holding friend in the dust when the market recovers.

You simply can’t save your way to riches. You have to invest. Our conservative saver with over $720,000 in the money market isn’t in dire straits … but had they invested that money in the stock market instead of sitting in cash, they’d have more than $3.8 million in their 401(k). That’s a very different proposition.

I should also add that you shouldn’t count on superior investment returns to bail out a low savings rate. It’s really the intersection of the two—a robust savings rate and investing—that allows you to harness the power of compounding.

Get Started

Even if you can only “start small,” it’s essential to start. Compounding takes time, so try to put as much time on your side as possible. Plus, it becomes a habit if you start saving and investing early. When you start earning more money and can sock away more money—when the stakes are higher—you’ll have more experience, and your saving and investing muscles will be up to the challenge.