Retirement investing—whether it’s decades off, approaching fast or you are there already—is daunting. The unfortunate truth is that many people facing this challenge have ignored it until late in the game.

Last week, in What Kind of Investor Are You?, I wrote about the mutual fund industry’s (Vanguard included) silver bullet for the retirement puzzle: life-cycle funds. At Vanguard, there is much to like about the firm’s Target Retirement series, which are low-cost, diversified and transparent. Investing in one of these funds is certainly a better long-term proposition than simply holding cash.

However, as I detailed last week, I have some serious issues with life-cycle funds’ one-size-fits-all philosophy. Basing an investment portfolio on one metric, your age, just doesn’t cut it, in my view.

That said, funds like the Target Retirement series have become a popular portfolio choice, particularly for retirement plans like 401(k)s and 403(b)s, where they are often the default option and occasionally the only option for plan participants.

So, let’s pop the hood on Vanguard’s life-cycle options—specifically, the Target Retirement as well as the LifeStrategy funds. After reading this, you’ll be able to make your own informed decisions about whether any of these one-size-fits-all funds work for you.

Key Points

- LifeStrategy funds have fixed allocations to stocks and bonds through time, while Target Retirement funds shift allocations over time.

- The funds are low-cost, diversified and straightforward.

- Buying a life-cycle fund based solely on your age could be a big mistake.

Static or Target

The basic premise (and promise) of a life-cycle fund is that with one purchase, an investor gets a broadly diversified portfolio that can be held forever—at least, the mutual fund companies hope you’ll hold it forever. One decision, and the investor is done for life. Can it get any easier?

Probably not. But it’s not as simple as the fund companies would have you believe. By my count, Vanguard offers 18 different life-cycle mutual funds, all of which are funds of funds, meaning their portfolios are built of other funds rather than individual stocks and bonds. These funds fall into one of two buckets: static allocation or target maturity strategies. So, how do you choose one over the other?

I’ll get to that, but first, some definitions. A static allocation fund is one where the allocations to the portfolio’s underlying investments remain the same at all times. If Vanguard’s prospectus says the fund will invest 10% of assets in cash, 40% in bonds and the remaining 50% in stocks, then that’s what it’s going to do, every day, month and year. As money is added to the fund or withdrawn, Vanguard’s allocators essentially rebalance the portfolios back to the stated percentages.

This type of fund might be best for someone who’s got a very clear idea of how much risk they are willing to accept relative to the returns they hope to earn. Because the allocation is set, you’re pretty much making one decision and then letting it ride. All the rebalancing is done for you, sometimes daily (depending on cash flows), which means you’ll always know how much of your money is tilted towards stocks versus bonds or bonds versus cash.

The four LifeStrategy funds and Retirement Income (VTINX) are static allocation funds. So is Balanced Index (VBINX), for that matter—I’ll take a broader look at Vanguard’s balanced funds in a future Funds Focus article. (Vanguard also offers static allocation funds of funds in its 529 plans, but let’s set those aside for another time, since investing for college is a different nut to crack compared with retirement.)

By comparison, 11 of the 12 Target Retirement funds (Target Retirement Income being the exception) are target maturity funds. These portfolios are geared towards retirement savers of varying ages. The idea is that you pick the fund with the year closest to when you expect to retire, and then you sit back and let Vanguard do the work of slowly moving your money from riskier (stocks) to less risky (bonds and cash) allocations over time.

With a Target Retirement fund, your allocations start off heavily tilted toward stocks and eventually converge to the same (30% stocks, 53% bonds, 17% cash) allocation as Target Retirement Income. At that point, they become static allocation funds and their assets are merged into the income fund.

A year ago, Vanguard merged Target Retirement 2015 into Target Retirement Income and launched a new fund, Target Retirement 2070 (VSVNX), around the same time.

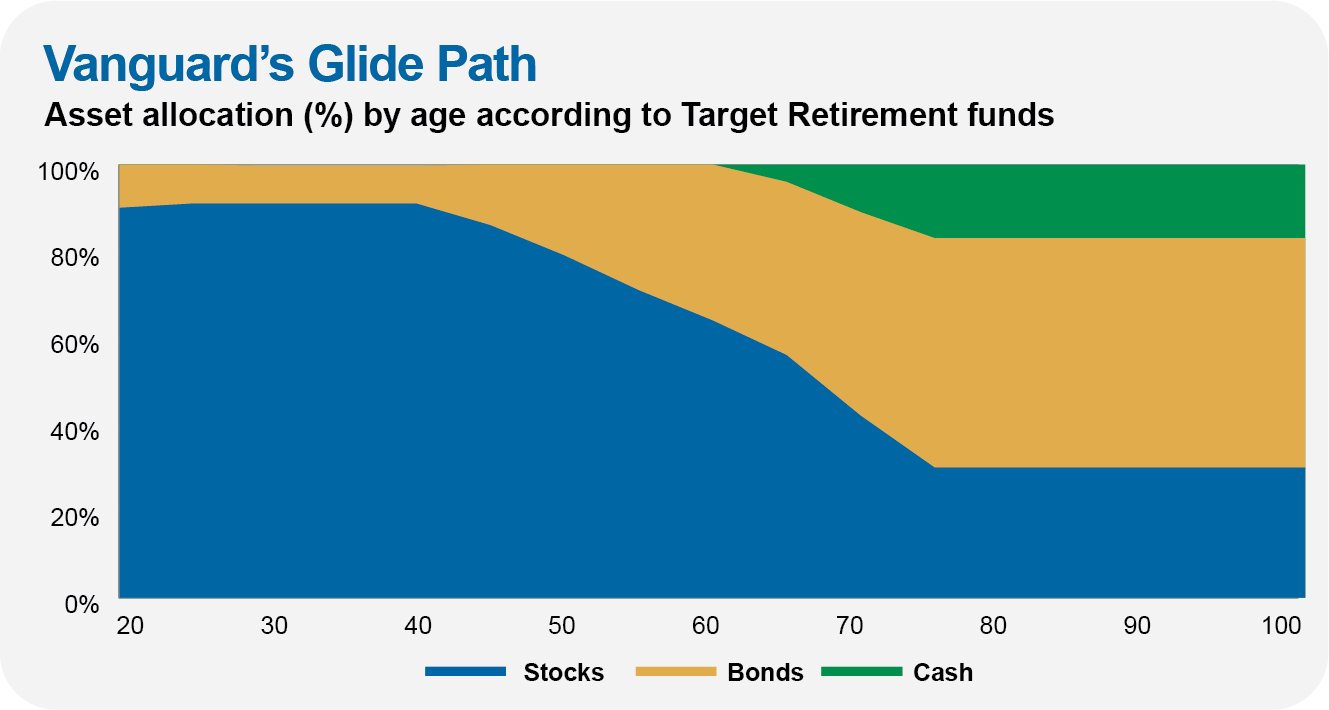

This shift from stocks toward bonds and cash over time is what’s known as a glide path. You can see Vanguard’s glide path in the chart below. (Note that while I list it as cash, technically Vanguard is using Short-Term Inflation-Protected Securities Index (VTAPX) instead of a money market fund.)

Not every company follows this glide path. If your 401(k) offers target-date funds run by T. Rowe Price or Fidelity (two of the biggest target fund providers) or someone else, you should pop the hood on the portfolios to see just how much they are allocating to stocks versus bonds and cash.

The simple idea behind the glide path is that investors want to reduce stocks as they get older and closer to making withdrawals. According to Vanguard’s glide path, everyone under the age of 40 should have 90% of their assets invested in the stock market. Then, as you move closer to retirement, everyone should reduce stock exposure and ultimately have about 55% of their assets in stocks when they retire (age 65 in the chart). You then continue to reduce your stock allocation for the next decade. From your 75th birthday on, Vanguard says you should hold 30% of your portfolio in stocks until you leave this earth.

You’ll notice in the preceding paragraph one of the basic faults with target maturity funds—they treat all investors the same, as if age is the only factor determining your investment portfolio. More on that in a minute.

Moving Target

Let’s go back to the static versus target fund question. This is important. I said that the companies offering these funds want you to think they are one-and-done investments. They’re not.

You see, once you’ve made your choice between a static allocation fund and one that gradually evolves over time, it’s critical that you keep an eye on the portfolio. Vanguard has made big and small tweaks to its funds several times (as have its competitors). They may say these are “set it and forget it” funds, but their own actions belie that characterization.

When the LifeStrategy funds were first introduced in 1994, Vanguard used a mix of index and active funds to construct their portfolios. That lasted over 15 years, but in 2011, the LifeStrategy funds switched to an all-index fund approach.

The changes didn’t stop there, though. In 2013, Vanguard added Total International Bond Index (VTIBX) to all four funds. Two years later, Vanguard boosted the allocation to both foreign stocks and bonds—today, foreign stocks make up 40% of each fund’s allocation to stocks and foreign bonds are 30% of the bond sleeves. Whether that’s what investors originally signed up for when they bought these funds, well, that’s the $34 billion question (about the amount of money investors had in the funds at the end of 2013).

Who said you could just set and forget the LifeStrategy funds?

The Target Retirement series has evolved, too. In their original configurations, the funds were considered “too conservative” compared to their competitors. Other fund families, particularly T. Rowe Price, were offering competing funds with more aggressive, better-performing portfolios.

Vanguard’s solution in 2006 was to cut back on bonds and add to both domestic and foreign stocks, including those from emerging markets. Target Retirement 2025 (VTTVX), for example, saw its allocation to stocks jump from under 60% to just over 80%, and bonds were cut in half from the original 40% allocation. That’s a big change in strategy. (Today, 17 years along its glide path, the fund’s stock allocation is down to 55%.) Similar changes were made along the entire Target Retirement series.

Target Retirement funds’ exposure to foreign bond and stock markets have increased over time, as well. In 2010, Vanguard hiked its foreign-stock exposure from 20% to 30% in most portfolios. In 2013, Vanguard added foreign bonds to the portfolios using the then-new Total International Bond Index. The most recent change came in 2015, when Vanguard boosted foreign stock and bond exposures to 40% and 30%, respectively. If you weren’t paying attention, well, Vanguard was making some pretty major strategic changes to your funds.

Actively Managing Indexes

As the table below shows, indexing is the bedrock of Vanguard’s life-cycle funds. After many changes over the years, virtually all of the strategies are currently built on a foundation of four index funds: Total Stock Market Index, Total International Stock Index, Total Bond Market Index and Total International Bond Index.

How the Allocators Allocate

| TR 2070 | TR 2065 | TR 2060 | TR 2055 | TR 2050 | TR 2045 | LS Gro. | TR 2040 | TR 2035 | TR 2030 | LS Mod. Gro. | TR 2025 | TR 2020 | LS Cons. Gro. | TR Inc. | LS Inc. | |

| Total Stock Market | 54 | 54 | 55 | 55 | 55 | 52 | 49 | 48 | 43 | 38 | 36 | 33 | 25 | 24 | 18 | 11 |

| Total Int'l Stock | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 34 | 32 | 31 | 28 | 25 | 24 | 22 | 17 | 16 | 12 | 8 |

| Total Bond Market | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 15 | 20 | 26 | 28 | 29 | 33 | 42 | 37 | 56 |

| Total Int'l Bond | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 19 | 16 | 24 |

| Short-Term Infl-Prot. Sec. Index | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 4 | 11 | — | 17 | — |

| Note: Percent of underlying funds as of May 31, 2023. Allocations may change over time. Funds listed in declining allocation to stocks. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. | ||||||||||||||||

To keep the table simple, I used the generic name of each “total market” index fund. However, look under the hood and you’ll see that Vanguard mixes and matches different share classes and versions of its total market funds. In the following table, I broke down the share classes used in the Target Retirement and LifeStrategy funds.

Mixing & Matching Share Classes

| Target Funds | LifeStrategy Funds | |

| Total Stock Market | Institutional Plus | Investor |

| Total International Stock | Investor | Investor |

| Total Bond Market | II (Investor) | II (Investor) |

| Total International Bond | II (Institutional) | II (Investor) |

| Short-Term Infl-Prot. Sec. Index | Admiral | -- |

This mishmash is wrong-headed. I’ve long argued that Vanguard should use the cheapest share class for each of these funds. Even if they are geared toward individual investors, the money being invested is mostly coming from 401(k)s, making it sticky and predictable.

Vanguard has made steps in the right direction, but they haven’t reached a satisfactory destination yet. Investors in the Target Retirement funds get access to the Institutional Plus shares of Total Stock Market Index (which charge just 0.02%) but still hold the costliest Investor shares of Total International Stock Index (0.17%). Why?

Owners of the LifeStrategy funds continue to be allocated into Investor shares for all of their holdings. This means that you could probably build your own LifeStrategy fund at a lower cost using Admiral or ETF shares of the underlying total market funds. In fact, why wouldn’t you?

Those “II” funds are clones of Total Bond Market Index and Total International Bond Index that Vanguard uses for internal purposes. Their argument is that the two-fund set-up protects the investors in the Target Retirement and LifeStrategy funds from being negatively impacted by inflows and outflows of other investors.

I can buy that … but if the “II” versions make sense for the bond funds, why not the stock funds?

The bottom line is that Vanguard could lower fees for investors in their life-cycle funds, if they wanted to. Why they don’t is a multi-million-dollar question.

Retirement or Lifetime Income?

Circling back to the first table above, the one exception to the “total” index fund strategy is the addition of Short-Term Inflation-Protected Securities Index, which you can find in the three most conservative Target Retirement funds. You won’t find that fund in the LifeStrategyportfolios, though.

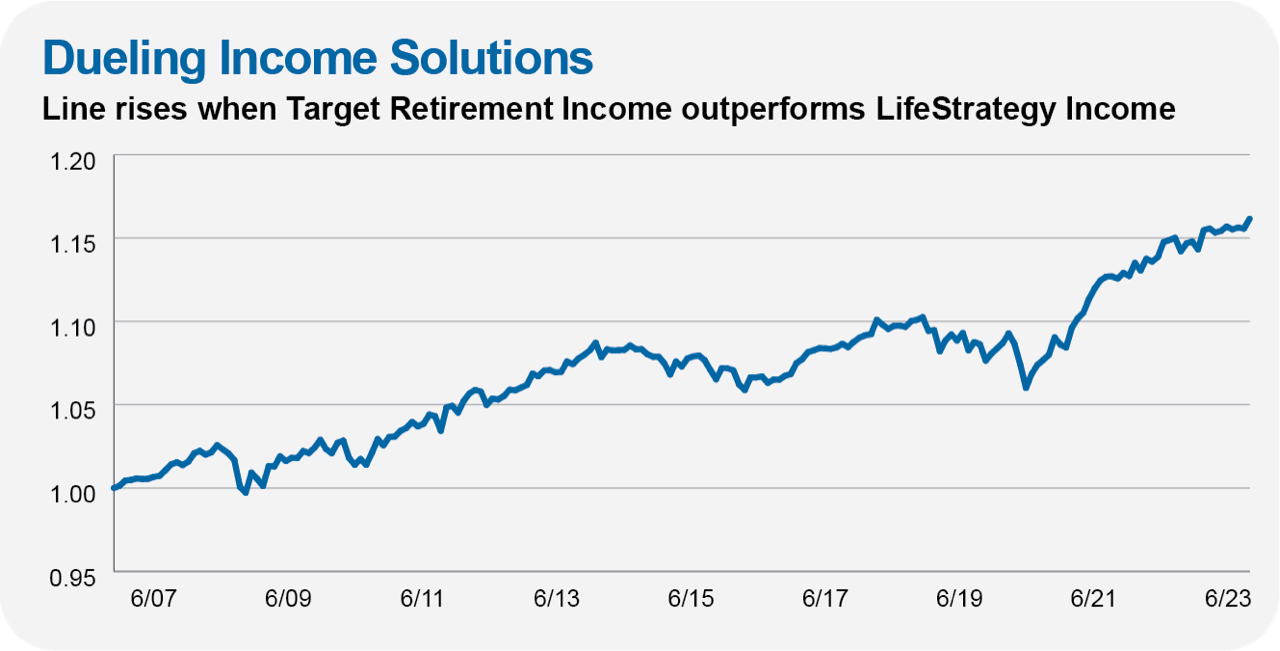

And here’s another place where confusion creeps in. Vanguard isn’t consistent in how an investor should go about generating retirement income. Compare Target Retirement Income and LifeStrategy Income (VASIX), which arguably have the same long-term income-generating goal in mind. The LifeStrategy fund allocates 20% of its portfolio to stocks, while the Target Retirement fund allocates 30%. One also has an allocation to Short-Term Inflation-Protected Securities Index, and the other doesn’t.

Which is the better fund for income? Well, neither is really designed to maximize the income paid out—neither portfolio is loaded up with the highest-yielding stuff out there. Both take more of a total return approach to generating “income” for life or retirement.

As you can see in the relative performance chart below, the Target Retirement Income fund has outperformed its LifeStrategy competitor. But then, that’s what I’d expect over time, given the higher allocation to stocks, despite both funds having “Income” in their names.

I lean in favor of the Target Retirement fund simply because of its higher allocation to stocks—even investors in their 70s need growth in their portfolio to protect against inflation. But, frankly, the difference between 20% stocks and 30% stocks isn’t that large. By offering both funds, Vanguard may be giving investors more choice, but this is a case where having more options isn’t better—it just leads to confusion and potential analysis paralysis.

Falling Behind?

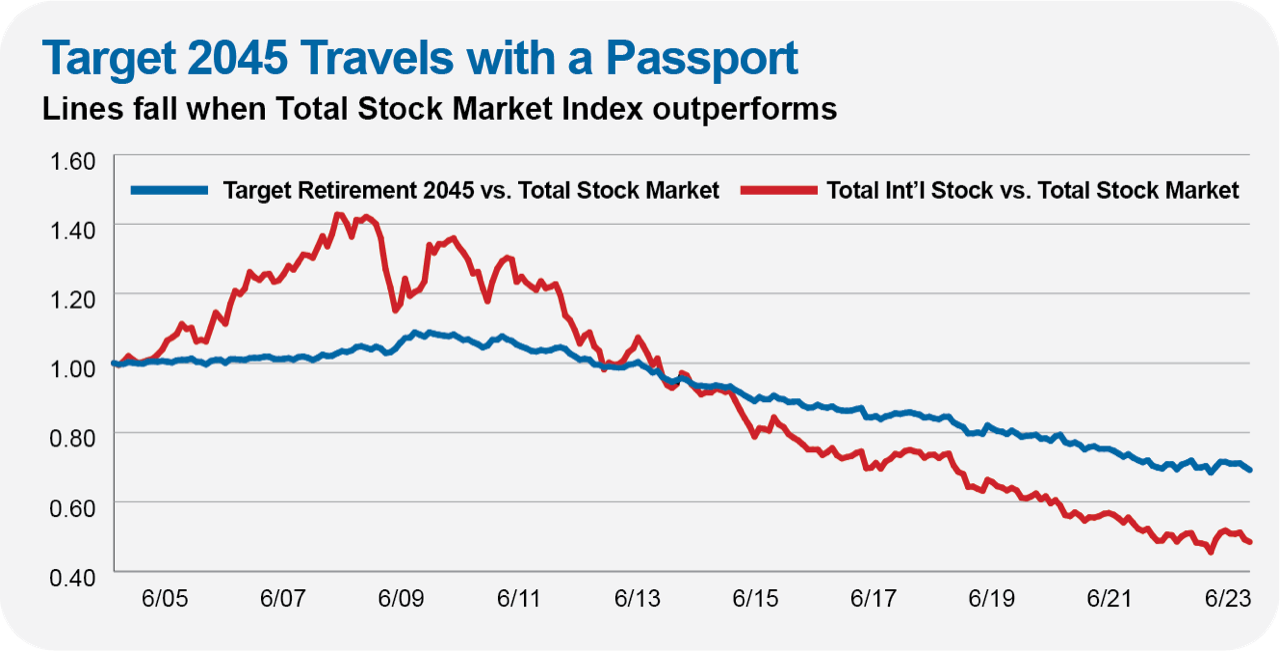

I often hear from investors who are frustrated that their Target Retirement funds haven’t kept up with the S&P 500. This is a big mistake in how investors should think about their life-cycle fund, no matter what its name or its provenance. Your Target Retirement or LifeStrategy fund isn’t broken—you’re just comparing apples to pears.

First off, your Target Retirement fund—even the ones with the longest dates—hold some of your money in bonds. So straightaway, you are comparing an all-stock portfolio (the S&P 500) to a portfolio that also holds bonds and cash (your target fund). It’s pretty simple: I’d expect the all-stock strategy to outperform in the long run.

Second, all of Vanguard’s Target Retirement funds are global portfolios, while the S&P 500 is only made up of U.S. stocks. And this is one area where Vanguard is doggedly consistent. All of its allocation funds push 40% of your stock money into Total International Stock Index—period. It wasn’t so long ago that 30% was the magic number at Vanguard. Today it’s 40% … regardless of fund or shareholder objective or risk tolerance.

This is something that doesn’t strike me as a particularly good thing, allowing the same level of currency risk to creep into the equity portfolio of an 80-year-old that you might find in a portfolio for a 20-year-old. That’s where consistency and simplicity seem to break down when it comes to driving the best outcomes for all investors.

But let’s get back to comparing your global target fund to the U.S.-only S&P 500. If foreign stocks are outpacing U.S. stocks, that’ll be a tailwind for all of the Target Retirement funds. But if U.S. stocks are leading the way (as they have for the past decade-plus), then the S&P 500 is virtually guaranteed to outperform a fund allocating significant sums to foreign shares.

You can see this in the following relative performance chart. I’ve compared Target Retirement 2045 (VTIVX) to Total Stock Market Index. (Why did I choose the 2045 fund, even though it’s on its way down the glide path, with about 15% invested in bonds? Because of the options that have a history dating back to 2003, it’s the most aggressive.) The second line on the chart tracks the relative performance of Total International Stock Index versus the U.S.-only index fund. The lines rise when the target date or foreign stock fund is outperforming and fall when Total Stock Market Index is outperforming.

The two lines follow a similar trajectory. In the 2000s, when foreign stocks were outpacing U.S. stocks, Target Retirement 2045 beat the U.S. stock index fund despite holding 10% of its portfolio in bonds. Over the past 15 or so years, however, foreign stocks have trailed U.S. stocks, weighing on Target Retirement 2045’s relative fortunes.

If you are measuring your investment success compared to the S&P 500, then your global target fund is going to fall behind at times and move ahead at others—that’s not a bug, it’s a feature of being diversified. If it really irks you to trail the S&P, then just buy 500 Index (VFIAX) and call it a day.

Building the Complex (and Complexities)

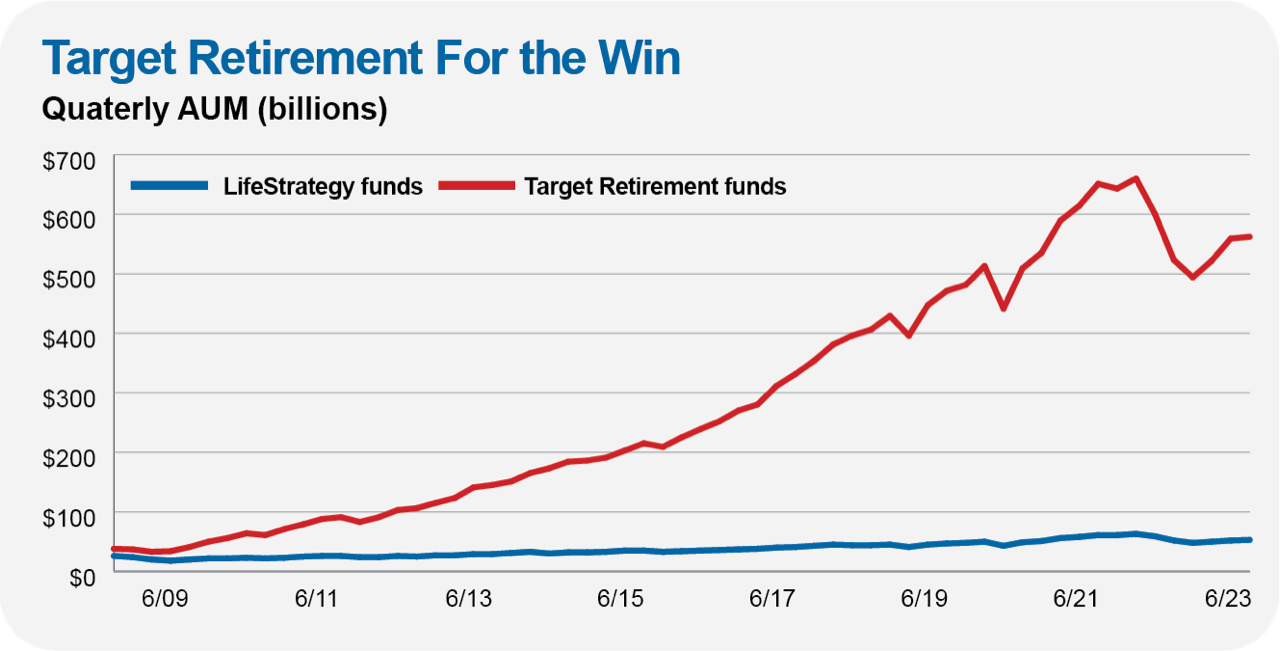

Vanguard’s funds of funds are a big business, and 401(k) plans in particular love target-date funds because human resources and benefits managers can use them as default positions for employees who don’t take an interest in their retirement accounts. Plus, it gets corporate managers off the hook for any liability if someone retires with less-than-adequate savings—at least they tried.

Don’t get me wrong—a target-date fund is an improvement over the old days, when the default option was cash, but this is lowest-common-denominator investing. And Vanguard loves it because the notion of set-it-and-forget-it makes assets very “sticky” and easy for the fund complex to administer. Plus, when it comes to retirement plans, the flows of new money are very consistent and predictable.

Typically, the Target Retirement funds hoover up assets month after month as automatic investments from 401(k) participants’ paychecks flow in. Consider that investors added more money to their Vanguard target-date funds than they took out every year since their 2003 inception through 2021—that’s a period that includes the global financial crisis and the COVID pandemic.

However, things went a bit haywire for Vanguard in 2022. For the very first time (on a calendar-year basis), investors pulled more money out of Vanguard’s target-date funds than they put in. The worst bond market in four decades pushed investors in the more conservative Target Retirement funds (2025 and 2020, in particular) to head for the exits.

At the end of May, assets in the 12 Target Retirement funds amounted to a bit more than $560 billion—up almost 4 times over the last decade. Meanwhile, the LifeStrategy funds’ assets have been relatively stagnant, up less than 2 times over the past decade—and most of that is thanks to the market, not a wave of new assets washing into the funds.

Crash Test

One lingering issue that I have with life-cycle funds isn’t so much with the funds themselves, but with the companies that offer them—Vanguard included. In my book, they get an “F” for educating investors about how to use these funds, relying too heavily on the buy-it-and-forget-it mentality. Especially in the early days.

First, according to Vanguard, Target Retirement funds are not meant to be held until you retire, at which point they are then sold; they are meant to be held throughretirement. I don’t think many early investors understood that.

Vanguard’s oldest Target funds weren’t around during the 2000 to 2002 bear market, for instance. So early investors in these funds, who may have relied solely on official, historical performance numbers, weren’t aware of the risks embedded in the target funds.

You could say that investors should’ve known better, but Vanguard believes that the Target Retirement funds are for “initial investors, not experienced or sophisticated investors.” The burden was (and is) on Vanguard to educate these clients about the risks involved.

However, if you were reading our original newsletter, you knew the risks … because we calculated them. Before the 2008 crisis hit, Dan had estimated the risks to Vanguard’s life-cycle funds based on the historical performance of their underlying funds. It wasn’t pretty, with many funds having the potential to lose almost 40% of their value. Vanguard didn’t talk about this at all.

When the financial crisis hit, the 2008 to 2009 market turned out to be even worse than the worst-case scenarios Dan had worked with! So maybe now investors are aware of the risks in their Target Retirement funds. Maybe.

The table below makes the risks in the LifeStrategy and Target Retirement funds clear by showing each fund’s drawdown during the past five bear (or nearly bear) markets. (For newer funds, I used their closest available sibling as a proxy.)

Be Ready for Bears

| Tech Bubble -2000-02 | Global Financial Crisis -2007-09 | COVID-19 -2020 | Great Reflation -2022-? | |

| LifeStrategy Growth | -35 | -48 | -18 | -23 |

| LifeStrategy Moderate Growth | -24 | -38 | -13 | -21 |

| LifeStrategy Cons. Growth | -12 | -28 | -9 | -19 |

| LifeStrategy Income | -4 | -16 | -4 | -17 |

| Target Retirement 2070 | -39* | -48* | -20* | -24* |

| Target Retirement 2065 | -39* | -48* | -20 | -24 |

| Target Retirement 2060 | -39* | -48* | -20 | -24 |

| Target Retirement 2055 | -39* | -48* | -20 | -24 |

| Target Retirement 2050 | -39* | -48 | -20 | -24 |

| Target Retirement 2045 | -39* | -48 | -20 | -24 |

| Target Retirement 2040 | -39* | -48 | -18 | -23 |

| Target Retirement 2035 | -39* | -48 | -17 | -22 |

| Target Retirement 2030 | -39* | -46 | -15 | -22 |

| Target Retirement 2025 | -35* | -42 | -13 | -20 |

| Target Retirement 2020 | -31* | -39 | -11 | -18 |

| Target Retirement Income | -4* | -17 | -7 | -16 |

| *Returns are estimated. Target Retirement tech bubble declines were estimated using the underlying holdings of the funds as of 2006. To fill in more recent gaps, I used drawdowns of the closest available Target Retirement fund. | ||||

| Current drawdowns assume that September 2022 was the monthly low in this bear market. | ||||

Again, it’s not pretty. While I don’t want you to let bear markets spook you from spending time in the markets, you do have to ask yourself two critically important questions before locking into a Target Retirement fund:

Is an all-index approach right for me? Would I rather have a set-it-and-forget-it portfolio that only shifts with the turning of the calendar (or a change in the thinking of Vanguard’s investment committee) or a portfolio that changes based on the market environment or my own evolving financial and life status?

More than a Number

And that’s where my issues with target funds stem from. Yes, for the most part, Vanguard’s life-cycle funds are straightforward, transparent, diversified, disciplined and cheap—all qualities that you want out of your investments. What’s not to like?

First, all of the underlying portfolio components are index funds. This denies investors the chance to invest in the very best funds with the best managers that Vanguard has to offer. I’d take an index fund run by Vanguard over the average actively managed mutual fund, but I’m not suggesting you, or Vanguard, should own the average fund. The PortfoliosI have built (and invest in) are proof that you can generate index-beating returns by partnering with the best Vanguard has to offer—active and passive.

Second, Vanguard has not been investor-friendly with its use of the more expensive Investor share classes of its index funds. They’re remedying the situation, but why has it taken so long … and whose bottom line is Vanguard really looking out for?

Third, at risk of repeating myself, a crucial flaw in the target date concept is that it assumes the only factor in determining how much to allocate to stocks versus bonds is your age. Age (or, really, your time horizon) certainly is one consideration, but it’s far from the only one.

By the time you’ve retired, your financial profile will probably look decidedly different from that of a coworker who is the same age and began working around the same time. Do you have the same incomes, savings, expenses? Do you have identical attitudes toward risk-taking? Probably not. How is it, then, that both of you have been investing exactly the same way and will continue to do so (if you stick with the Target Retirement Income fund)? It just doesn’t make sense.

What’s missing, of course, is the ability for the investor to remake or fine-tune their allocation. Again, life-cycle funds are investing made simple. Investing doesn’t need to be complicated, but every investor is different.

The Bottom Line

You could do a lot worse than investing in one of Vanguard’s life-cycle funds. But at the end of the day, I don’t believe that one-size-fits-all investing works. It doesn’t have to be complicated, but I think with a little extra effort, it’s possible to get better results tuned to your individual needs.

Partnering with the best managers in Vanguard’s stable and spending time in the markets has proven to be a winning formula. My three long-running Portfolios (excluding the index-only version) are a testament to the strategy of investing with Vanguard’s best funds and eschewing its lowest common denominator options. I’m investing for my own retirement right now, and I’ll continue to invest my money in the Portfolios, not in a pre-determined index fund amalgam. You should follow my lead.