Executive Summary: This is the second of a two-part series delving into the longstanding Wall Street advice to "not fight the Fed.” This analysis considers the conventional wisdom from the standpoint of a stock investor. Should an investor buy stocks if the Fed is cutting interest rates? In this case, the data does not support the theory. An updated strategy suggests getting defensive when the Fed first cuts interest rates but re-entering the market once substantial support is provided. Ultimately, a diversified, long-term approach remains effective, regardless of Fed actions.

Well, we are one week closer to the Federal Reserve’s September (17–18) meeting, at which it’s all but a foregone conclusion that policymakers will lower the federal funds target rate.

Conventional Wall Street wisdom cautions investors against “fighting the Fed.” Last week, I put that adage to the test from the standpoint of a bond investor. I found that the data validated the theory—you generally wanted to own bonds over cash when the Fed was supportive (cutting interest rates) but preferred cash when policy was restrictive (rising interest rates).

However, stock investors are also often told not to fight the Fed. So, I’m not done putting the adage to the test.

When it comes to the Fed and stocks, the thinking is that when policymakers are hiking interest rates—trying to slow the economy and inflation down a bit—you should avoid the stock market. But when the Fed is cutting interest rates to support the economy, you want to be in the market.

Or so the saying goes.

So, let’s dig into whether you should follow the Fed’s moves with your entire portfolio … or not.

Key Points

- Conventional wisdom says stocks should perform poorly when the Fed is restrictive (raising interest rates) and perform well when the Fed is supportive (lowering interest rates).

- The conventional wisdom is not supported by data over the past five decades.

- Stocks have compounded at double-digit rates while the Fed was restrictive.

- For the past three cycles, the Fed cutting interest rates has been a better sell signal than a buy signal.

- Ignoring the Fed is a viable strategy.

A Quick Methodology Recap

As a reminder, the first step in my process involved identifying periods since the end of 1976 when the Fed was either supportive or restrictive. I used judgment (and the benefit of hindsight) when identifying each phase in the cycle.

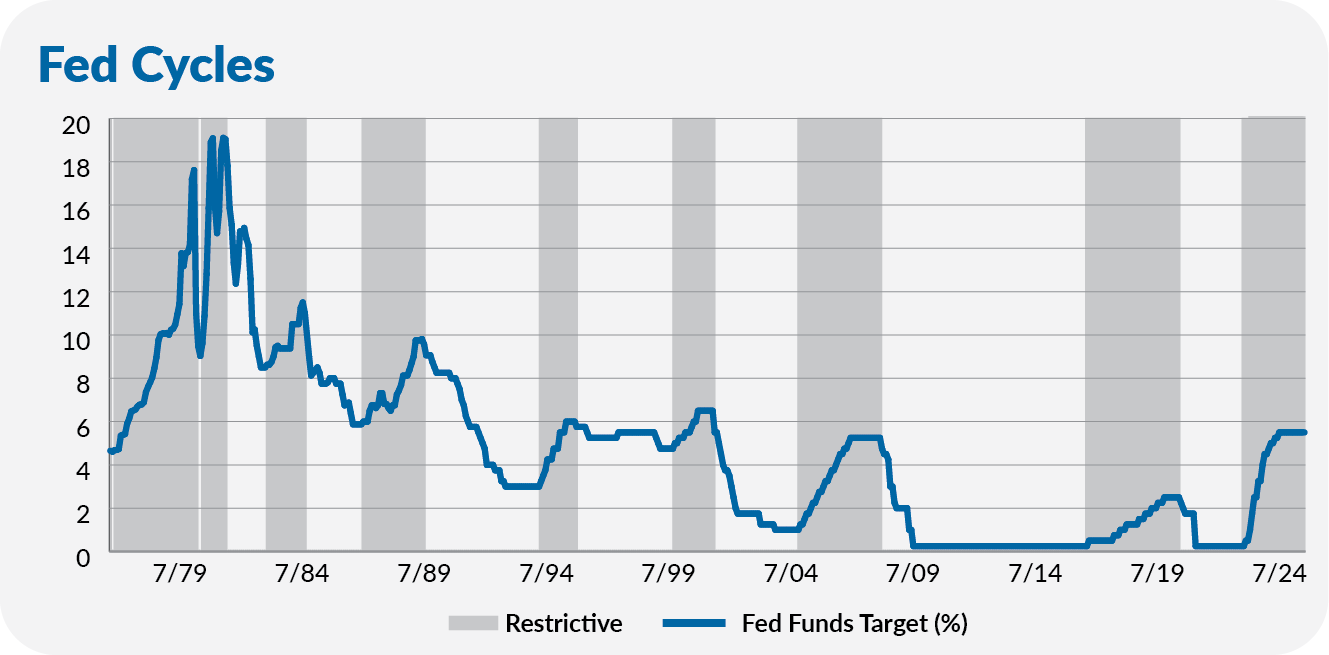

The chart below indicates restrictive Fed policy from the time policymakers started raising the fed funds rate until they started cutting it. Conversely, Fed policy is considered supportive from the Fed’s first interest rate cut until its first interest rate hike.

This broad definition of restrictive and supportive phases includes periods at the end of the cycle when policy was “on hold”—the fed funds rate held steady. So, as I did last time, I’ll make a separate analysis that considers only those periods when policymakers were actively hiking or lowering interest rates.

Throughout this analysis, I’m using monthly data. I used 500 Index (VFIAX) as my proxy for stocks, and the same benchmarks as last time for bonds and cash. For bonds, I combined Long-Term Investment-Grade (VWESX) and Cash Reserves Federal Money Market (VMRXX) from 1977 through 1986. At that point, I switched to Total Bond Market Index (VBTLX). Cash Reserves Federal Money Market is my yardstick for cash.

And, like last time, I’ll focus on average annualized returns in the charts and commentary. More detailed tables are included in the appendix.

Should a Stock Investor Follow the Fed?

The story isn’t straightforward when it comes to stocks.

If the “don’t fight the Fed” adage is correct, then stocks should perform poorly when the Fed is restrictive and should deliver better returns when the Fed is supportive.

The chart below shows the average annualized returns of stocks, bonds and cash during the different phases of the Fed cycle. (This is the same chart as last week, with stock returns added to the mix.)