Executive Summary: This is the first of a two-part series delving into the longstanding Wall Street advice to "not fight the Fed." This analysis considers the conventional wisdom from the standpoint of a bond investor. Should an investor buy bonds if the Fed is cutting interest rates? In this case, the data backs up the theory—that bonds generally outperform cash when the Fed is supportive—but that doesn’t mean you should load up on bonds.

Federal Reserve (Fed) policymakers will (almost certainly) cut interest rates in September. Cause for alarm? I don’t think so.

That doesn’t mean the noise surrounding this decision won’t be heating up over the coming weeks. I’m already getting comments and questions, including notes like this:

I need to know what to do when the Fed causes yields to crash.

The easy answer, if you truly think that bond yields will crash, is that you should buy long-maturity bonds—Extended Duration Treasury ETF (EDV) will give you the most bang for your buck among Vanguard’s funds, as it is the most sensitive to changes in interest rates.

But that answer isn’t fully satisfying, and it assumes that crashing yields are in the cards. (I think that’s extreme and highly unlikely.)

Instead, let’s take this moment of (relative) calm to arm you with facts to counter some of the emotions that may be driving this kind of thinking. How concerned should investors be when, not if, the Fed begins to lower interest rates? Or, more generally, should investors adjust their portfolios in response to changes in Fed policy?

Common Wall Street wisdom has always held that investors shouldn’t “fight the Fed,” implying that they should align their portfolios with the Fed’s monetary policy.

This adage applies to both stock and bond investors, so let’s examine it in two parts: This week, I’ll examine the “advice” from the standpoint of a bond investor. Next week, I’ll incorporate stocks into the equation.

The relationship between Federal Reserve policy and bonds seems pretty straightforward. Since bond prices rise when interest rates fall, interest rate cuts should be a recipe for increasing bond values. The opposite would hold—the Fed raising interest rates should lead to lower bond prices.

So, if we were to “follow the Fed” with our bond portfolios today, we’d favor bonds—particularly long-maturity bonds—over cash (think money markets).

I’m skeptical that such a simple and obvious strategy will yield reliably profitable results. But let’s put my skepticism aside and put the common wisdom to the test.

Key Points

- Common Wall Street wisdom tells investors to own bonds when the Fed is supportive (cutting interest rates) and to hold cash when the Fed is restrictive (hiking interest rates).

- The data backs up this rule of thumb … at least when aided by the benefit of hindsight.

- It's hard to know where we are in the cycle in real time, and making a big one-way bet may not suit all investors.

- Investors who ignored the Fed still earned reasonable returns over time.

Cutting Through the Jargon

Before diving in, a quick word on jargon.

Whether it’s the media or investment commentary from economists and strategists, there’s a lot of shorthand language about Fed policy.

When the Fed heads are lowering interest rates, monetary policy is said to be “easing,” “easy,” or “accommodative.” On the flip side, the Fed is said to be “tightening” policy when raising interest rates. Personally, I prefer to say the Fed is either “supportive” or “restrictive,” but all have their uses.

Also, remember that the Fed does not control all interest rates. Policymakers only directly target a level for the fed funds rate, which is important as a benchmark interest rate that influences other lending rates. However, Fed policymakers do not directly control the yield on, say, the 10-year Treasury bond.

Now, back to whether you should follow the Fed’s moves with your investments … or not.

The Cycles

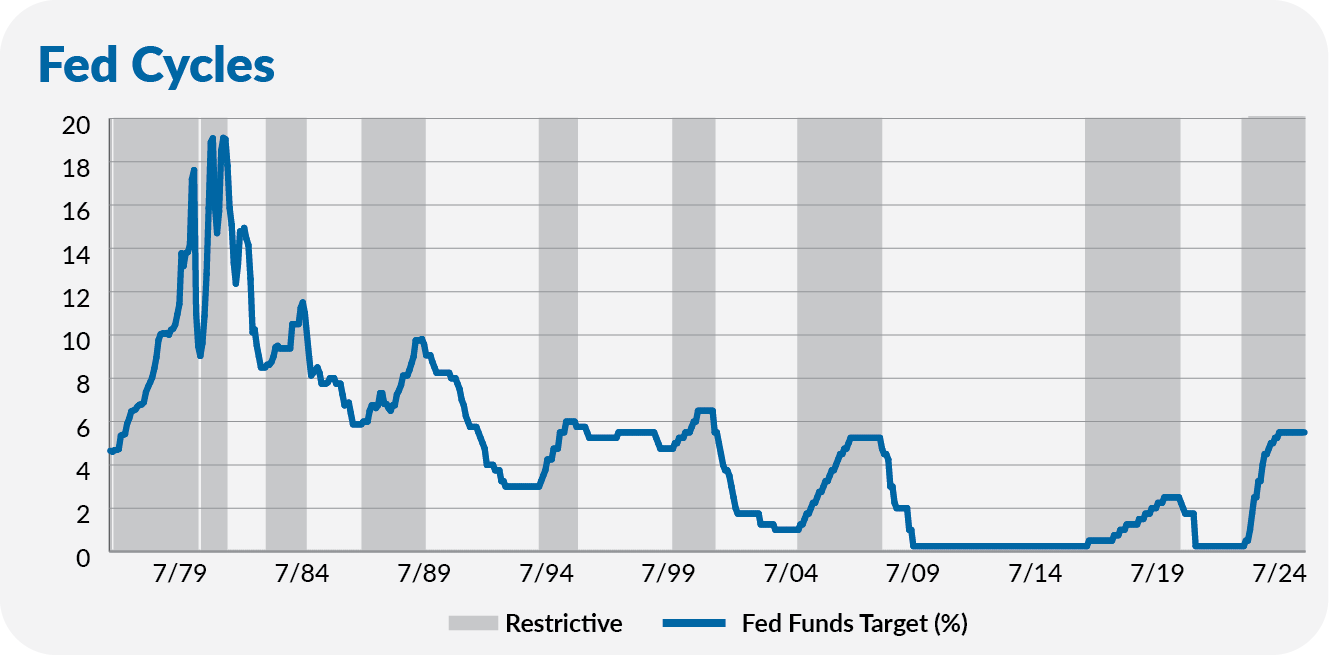

As a first step, I’ve identified periods since the end of 1976 when the Fed was either supportive or restrictive. I chose this start date because it roughly coincides with the beginning of a restrictive phase in the cycle (February 1977) and the inception of 500 Index (VFIAX, August 1976). I want to analyze investable Vanguard funds, and (again) I’ll incorporate stocks into the equation next week.

I’ve used some judgment (and the benefit of hindsight) in identifying these cycles.

For instance, I’m ignoring the Fed's one-time bump from 5.25% to 5.50% in March 1997—that’s a tweak, not a cycle.

Also, policymakers at the Fed were much (much) more active in the 1980s than they have been for the past three decades—often raising interest rates for a month or two, only to reverse course. This makes it more difficult to identify the different cycles, but I tried to ignore the month-to-month noise and focused on the general trend of the fed funds rate.

For example, the Fed cut interest rates for four months in late 1987 and early 1988 (from 7.31% to 6.25%), but that was when they were generally hiking interest rates, so let’s call that one cycle rather than splitting it in two.

However, I took the opposite view on policymakers’ decision to cut the fed funds rate from 17.61% to 9.03% in three months in 1980. The fed funds rate was back near 20% within the year, so you can argue for that being one cycle. But in my book, cutting the fed funds rate in half counts as a break in a restrictive cycle—albeit a brief break.

In the chart above, I’ve identified Fed policy as restrictive—the rate-hiking objective—from when policymakers started raising the fed funds rate until they began cutting it. This means that it often includes periods at the end of the cycle when policy was “on hold”—the fed funds rate held steady for a period before the next cycle of rate cutting.

Conversely, Fed policy is supportive from the Fed’s first interest rate cut until its first interest rate hike, which may also include times when policymakers held the fed funds rate constant.

Because you may want to know about only those periods when the Fed was actively hiking or lowering rates, not when they were standing pat, I analyzed the impact on our investments both ways.

As we turn to the data, keep two important caveats in mind:

First, as I said, I’ve identified these cycles with the benefit of hindsight. It is much more difficult (if not impossible) to know where in the cycle you are in real time—particularly at the turning points.

Second, we only have eight and a half Fed cycles to analyze. So, take this analysis with a “small sample”-sized grain of salt.

The Methodology

I used monthly data for this analysis, so I am not measuring returns from the exact day policymakers acted. If following this approach only works if you trade on the specific days the Fed acts, then the strategy operates on slim margins.

I combined Long-Term Investment-Grade (VWESX) and Cash Reserves Federal Money Market (VMRXX) to measure bond returns from 1977 through 1986. At that point, I switched to Total Bond Market Index (VBTLX). I used Cash Reserves Federal Money Market for, well, cash.

In the chart and commentary below, I’ll focus on the average annualized returns earned by bonds and cash during the different phases of the Fed cycle. This allows us to compare cycles of differing lengths on equal footing.

If you want to go deeper (or want me to “show my work”), I’ve included tables in the appendix detailing how bonds and cash performed during each cycle using annualized and total returns.

With that, let’s get to the heart of the matter.

Should a Bond Investor Follow the Fed?

If common wisdom is correct, cash will beat bonds when the Fed is restrictive (raising interest rates). Conversely, bonds should beat cash when policy is supportive (the Fed is cutting interest rates).

In the chart below, I have plotted the average annual returns earned by bonds and cash during the different phases of the Fed cycle.