Hello, this is Jeff DeMaso with the IVA Weekly Brief for Wednesday, March 15.

There are no changes recommended for any of our Portfolios. This week’s Weekly Brief runs longer than normal, but there is a lot to unpack given the recent bank failures and market volatility.

Is My Money Safe?

That’s the fundamental question I heard most often this week as Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank failed over the weekend. And the headlines in search of the next bank failure—Credit Suisse is in the spotlight today—aren’t helping investor confidence.

My short answer is, yes, I believe our investments and cash at Vanguard to be safe. Of course, the value of our investments will rise and fall through time. And yes, markets are stressed and confidence in banks is low right now. But it doesn’t seem to me that we are on the precipice of a widespread financial crisis. Let me explain.

Both SVB and Signature collapsed due to bank runs. One of the best explanations of a bank run comes from It’s A Wonderful Life.

When you deposit money at a bank, they don’t just put your money in the vault and wait for you to withdraw it. Banks lend your money out to earn a return on your money—paying you a low interest rate and earning a higher interest rate is how banks make money. Banks typically keep enough cash on hand to meet regular withdrawals, but if everyone asks for their money at the same time, well, there simply won’t be enough cash there for everyone.

As long as customers have confidence in the bank, then all is well and good. But when depositors lose confidence that the bank will be able to return their money, they scramble to get their money out before the coffers run dry. If enough people lose confidence, you get a run on the bank.

Bank runs can spiral out of control and jump from bank to bank. However, Signature Bank and SVB weren’t your average banks.

Signature got caught out lending to the crypto sphere while SVB had a concentrated customer base (think start-ups and tech companies) with very large cash balances—some 80%-90% of SVB’s deposits were above the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) $250,000 insurance limit. If your money is not insured, you are going to head for the exit at the first whiff of smoke, even if there isn’t a fire.

That whiff of smoke at SVB came in the form of the bank selling some of its Treasury bonds at a loss. The bank got a big influx of deposits in 2020 from tech companies and bought Treasury bonds when rates were low. The price of those Treasurys fell as interest rates rose. If SVB could have held those Treasurys to maturity, they would have gotten their principal back and there wouldn’t have been any problems. But they were forced to sell before the bonds had a chance to recover.

Of course, any bank is certain to have some long-maturity Treasury bonds on its books. But SVB had a lot more than the average bank—about double. Plus, it appears that SVB did not hedge the risk of rising interest rates properly.

(I’ll be discussing this topic of rising interest rates and bonds in the next installment of my Bonds 101 series. In short, rising interest rates are a problem if you own long-maturity bonds but need the money in the near term … which is the position SVB was in.)

The government responded aggressively over the weekend, choosing to make all depositors whole—even those with over $250,000 in their accounts. The Fed also said they would loan money to banks against their Treasury bonds as if those bonds were trading at their original prices—removing the need for banks to sell bonds at a loss.

We can debate whether this is good or bad in the long run, but it should act as a firestop to other bank runs.

I want to call out an important distinction between failures in the regular financial system and the crypto sphere. When FTX (the crypto exchange) went under last year, customers were more or less out of luck. When a regulated bank fails, the regulators can step in and make depositors whole in a matter of days.

Full Faith & Credit

Still, I’ve heard some worries about FDIC-insured accounts on the grounds that the insurance will run out. It doesn’t really work that way. FDIC insurance is backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. If the insurance runs out, the government would find other means of backing those deposits.

In this light, an FDIC-insured account is the same “credit risk” as buying a Treasury bill or, say, Treasury Money Market (VUSXX). I know, the money market fund isn’t guaranteed, but its holdings are. Plus, Vanguard is deeply committed to keeping its money market funds in good standing with a $1.00 NAV—consider that the firm waived tens of millions of dollars in fees to keep money market yields above 0.00% for years.

Of course, another bank could fail in the days or weeks ahead, but when it comes to my money, with less than $250,000 in an FDIC-insured account, I feel my bank balance is safe and secured. If I had more than that, then I would diversify my cash holdings—I wouldn’t count on the unlimited insurance cap unless the rules officially change. But that need to diversify was there before SVB and Signature Bank went under. The CFOs with millions of dollars sitting in one un-insured account, well, they should have known better.

Whether I’d even want to have that much sitting in cash is another question. My Schwab checking account pays next to nothing in interest. Why wouldn’t I move some to, say, a money market or ultra-short-term bond fund? (I recently told Premium Members how I manage my cash.)

A Run on My Mutual Fund?

Could there be a run on a money market fund or other mutual fund? Yes … it has happened before.

The fund that comes to mind when I think of a “mutual fund run” is Third Avenue Focused Credit. This junk bond fund invested in low-quality and distressed debt. When shareholders asked for their money back, the fund wasn’t able to find buyers for the bonds it held and therefore wasn’t able to meet those redemption requests. Third Ave closed the fund and took nearly three years to return money to shareholders.

That’s the worst scenario I’ve seen in the mutual fund industry in nearly two decades. Frankly, I don’t see it happening at Vanguard. The Third Ave fund made the mistake of buying illiquid bonds in a daily liquid fund. It’s worth pointing out that this “run” was limited to this one specific fund and even other funds run by the Third Avenue fund family continued to operate normally.

However, I think a run on a Vanguard fund is unlikely. On top of that, given that Vanguard's funds are not full of illiquid securities (think distressed debt or private companies), even if a lot of shareholders demanded their money back at the same time, I would expect Vanguard to be able to meet those redemptions.

If every investor in a fund asked for their money back at the same time, the fund managers would have to liquidate the portfolio—selling stocks or bonds to raise cash. It wouldn’t be pretty, and the stocks or bonds would probably be sold at less-than-ideal prices, but investors would get their money out.

The one place fund investors won’t stomach a lower value for their shares is money market funds. Vanguard’s money market funds have stood the test of time and survived numerous crises—the S&L crisis of the 1980–1990s, the bursting of the tech bubble, the Global Financial Crisis, wars, pandemics, etc.—while maintaining a $1.00 NAV.

Plus, as I said, Vanguard has gone to great lengths to keep their money market funds in good standing.

Even if a Vanguard money market fund “broke the buck” (traded below $1.00 NAV)—which, again, isn’t something I expect to happen—we are probably talking about the NAV falling a few pennies, not a complete loss of value.

Is Vanguard Safe?

Vanguard is once again pushing customers out of legacy mutual fund accounts and into brokerage accounts. So, what if Vanguard’s brokerage fails?

First, the chances of Vanguard failing are miniscule. That said, let’s talk about brokerage accounts for a minute.

Brokerage accounts are not backed by the FDIC but by the Securities Investor Protection Corp (SIPC), which protects accounts up to $500,000. However, it isn’t there to make up losses on your investments, but to ensure that your investments are accounted for.

Crucially, brokerage firms are required to keep customers’ accounts separate from the firms’ accounts. This means that if the firm fails, your account should be just fine. And in most instances, when a brokerage firm goes under, SIPC “simply” arranges the transfer of accounts to a different brokerage firm.

That’s it. Vanguard’s Brokerage goes under and your accounts get moved to, say, Fidelity.

(To draw a comparison to FTX again, this is one way the crypto exchange went awry: Customer assets were used by the firm for trading purposes.)

SIPC insurance only really kicks in if the accounts can’t be transferred—in the case of theft or fraud. The liquidation process is messier than just moving accounts, but you can expect a check or shares from SIPC in that scenario. If you want to read more about what happens when a brokage firm fails, I found FINRA’s article to be among the more accessible.

It’s worth adding that according to Vanguard’s Brokerage Account Agreement, they “maintain additional coverage through an insurer that supplements the SIPC coverage available to Securities.” How important that extra level of insurance is, is hard to say … but it’s there.

The bottom line for me is that I’d be less anxious about being “over” the SIPC-insurance limit in a brokerage account than I would with an FDIC-insured cash account. I suppose at some asset level, it might be worth diversifying brokerage firms, but I wouldn’t be opening account after account to stay under the limit.

As for those legacy mutual fund accounts, they are not protected by SIPC. Reading the disclosures, here is how Vanguard describes the difference:

Vanguard funds not held in a brokerage account are held by The Vanguard Group, Inc., and are not protected by SIPC. Brokerage assets are held by Vanguard Brokerage Services, a division of Vanguard Marketing Corporation, member FINRA and SIPC.

Is it safer to have your assets held by The Vanguard Group without SIPC protection or by Vanguard Marketing Corporate (which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Vanguard Group) with SIPC protection? I’d say the SIPC protection makes the difference—after all, it’s hard to imagine a world where Vanguard’s brokerage operation fails but The Vanguard Group skates by unharmed.

The Good and the Bad

When SVB failed, I popped the hood to see which Vanguard funds held the bank’s stock, or more specifically the bank’s parent company’s stock, SVB Financial Group (SIVB).

The short answer is that it was held by the index funds and ETFs. The only active fund I saw that owned shares in the bank was Growth & Income (VQNPX)—and with three quant funds and over 1,600 holdings, that “active fund” is pretty much an index fund!

It may surprise you to learn that SVB was part of the S&P 500—though not a household name, it was the nation’s 16th largest bank. That said, SVB was a small holding in the index funds. At the end of January, it was just a 0.05% position in S&P 500 ETF (VOO) and a 0.04% position in Total Stock Market ETF (VTI). In isolation, the bank going under had little impact on the index funds and ETFs. The subsequent decline in price at other, larger banks and financial institutions had a bigger effect on the funds’ values.

This comes with the territory of owning an index fund—particularly Total Stock Market ETF. If you own the market, you are guaranteed to own the winners … but you’ll also own all the losers, too.

Flight to Safety

I have one last point to make (for now) on the bank failures—bonds are delivering as portfolio buffers. And in particular, Treasury bonds—despite the debt ceiling debate (which no one seems to be talking about right now)—are still the flight-to-safety asset of choice.

The impact of the bank failures is still playing out, but let’s just consider three trading days—Thursday, March 9, through Monday, March 13. Over this period, 500 Index (VFIAX) fell 3.4%. Small- and mid-cap stocks fell further, and the hardest-hit sector was financials—Financials ETF (VFH) was off 10.5%.

The best-performing fund in Vanguard’s stable was Extended Duration Treasury ETF (EDV), with a gain of 4.5%. Think of that fund as exposure to Treasury bonds on steroids. But high-quality bonds in general held their ground during this three-day period, as Total Bond Market Index (VBTLX) gained 2.2%.

Also note that the defensive stock holdings in my Model Portfolios held up relatively well. Dividend Growth (VDIGX) slid just 2.2%, while Health Care ETF (VHT) was off just 1.2%.

Of course, I’m just talking about three trading days, but it provides a moment to confirm if the more defensive holdings in our portfolios are delivering when we need them—they are.

Inflation Check-In

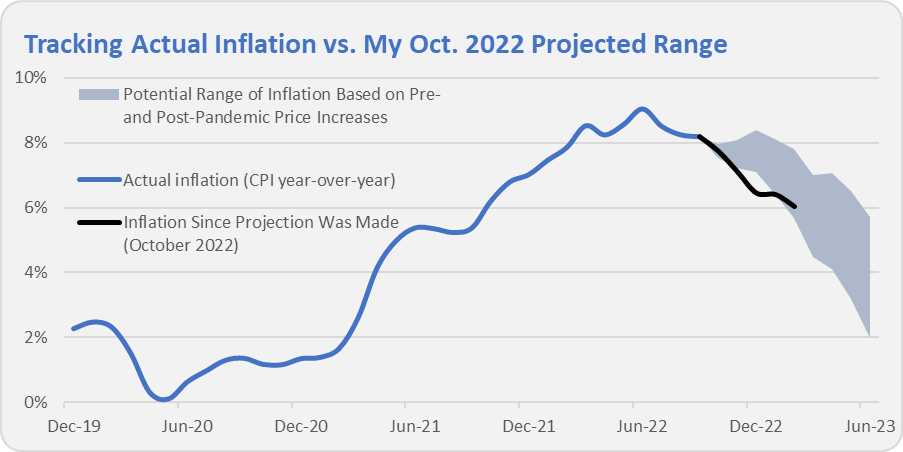

As I’ve been doing regularly for several months, let’s compare actual inflation to the range I set out back in October.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), consumer prices jumped 0.4% in February, and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is up 6.0% over the past twelve months. That keeps inflation to the lower end of my projection. And if the recent pace of price increases holds steady, we can expect inflation to clock in around 4% in the middle of the year.

Last week, we also got an update on the jobs market. While the economy added 311,000 jobs in February, the unemployment rate ticked up to 3.6% as more people returned to the labor force.

With Inflation around 6% and the unemployment rate below 4%, you’d expect the Fed would hike the fed funds rate and unemployment when they next meet week. We’ll have to see if the turmoil in the banking sector gives Fed Chair Powell and his colleagues enough reason to pause.

Supplemental Update

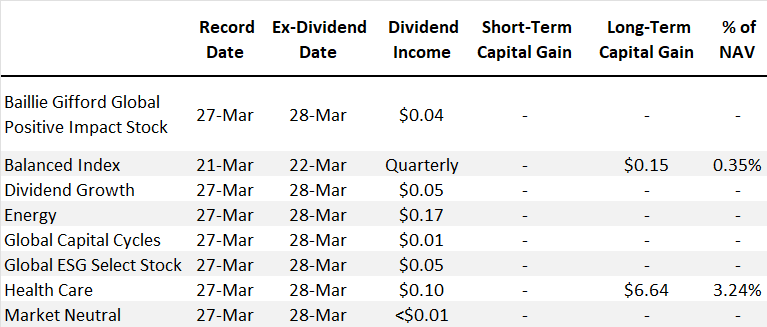

Last week, I shared the list of Vanguard funds that typically pay out income in March. As an update, Vanguard provided estimates of funds that will pay out supplemental income and capital gains in March.

I’ve summarized the funds in the table below and provided Vanguard’s official release. Only one fund, Health Care (VGHCX), is expecting to payout a meaningful amount in capital gains—equal to about 3% of the fund’s NAV. Balanced Index (VBIAX), in addition to paying out income as it usually does in March, will also make a small capital gain distribution of about 0.35% of the fund’s NAV.

A handful of other funds—Dividend Growth (VDIGX), Energy (VGENX), Global Capital Cycles (VGPMX), Global ESG Select Stock (VEIGX) and Market Neutral (VMNFX)—are set to pay out a little bit of income in the final week of the month.

In Vanguard’s release they include two institutional index funds that will distribute income and gains in the next few weeks. I’ve excluded these because the multi-million investment minimums put them out of reach of us mere mortals, so if you do own them, it’s probably through a retirement account where taxes aren’t an issue.

Our Portfolios

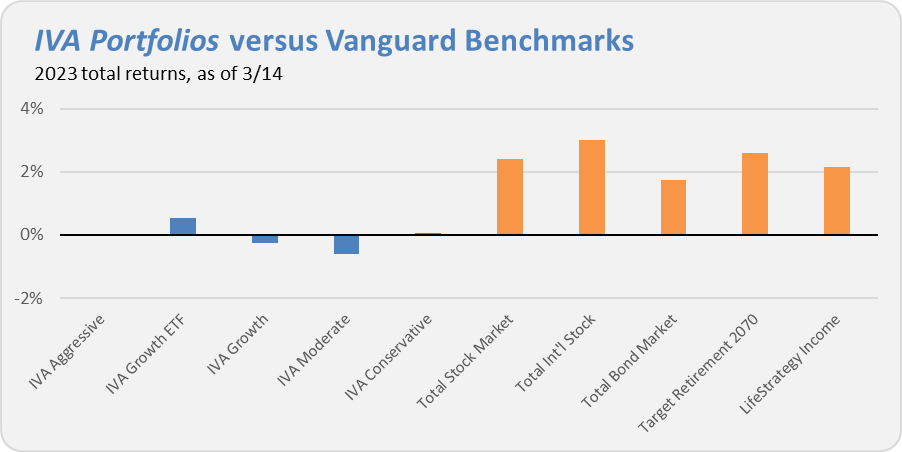

Our Portfolios are roughly flat this year, with returns ranging from down 0.6% for the Moderate Portfolio to up 0.5% for the Growth ETF Portfolio through Tuesday.

This compares to a 2.4% return for Total Stock Market Index (VTSAX), a 3.0% gain for Total International Stock Index (VTIAX), and a 1.7% return for Total Bond Market Index (VBTLX). Vanguard’s most aggressive multi-index fund, Target Retirement 2070 (VSNVX), is up 2.6% for the year, and its most conservative, LifeStrategy Income(VASIX), is up 2.2% for the year.

Until my next Weekly Brief, this is Jeff DeMaso wishing you a safe, sound and prosperous investment future.