We’ve hit the debt ceiling, and the shot clock is counting down on the U.S. government’s ability to pay its bills. The political negotiations are taking place both in the headlines and behind closed doors.

I never intended to write a political newsletter (and I won’t), so let’s set the politics aside. Instead, let’s look at the debt ceiling with our investor hats on and our portfolios in mind.

Key Points

- The Congressional limit on how much the U.S. government can borrow (the debt ceiling) means the government is at risk of defaulting on its obligations.

- Despite the political posturing, my base case assumption is that a deal will be struck and the U.S. government will not default.

- If you are going to upend your portfolio, keep it simple (think cash) and have a plan to get back into the market.

- In my own account, I’ll be putting cash to work systematically over the next few months.

What Is the Debt Ceiling?

The debt ceiling is the Congressional limit on how much the U.S. government can borrow to fund its operations.

Those operations cover a wide range of projects and programs, from Social Security to national defense to education and much more. Where does our government get the money for this spending? The first place is taxes. But taxes aren’t enough.

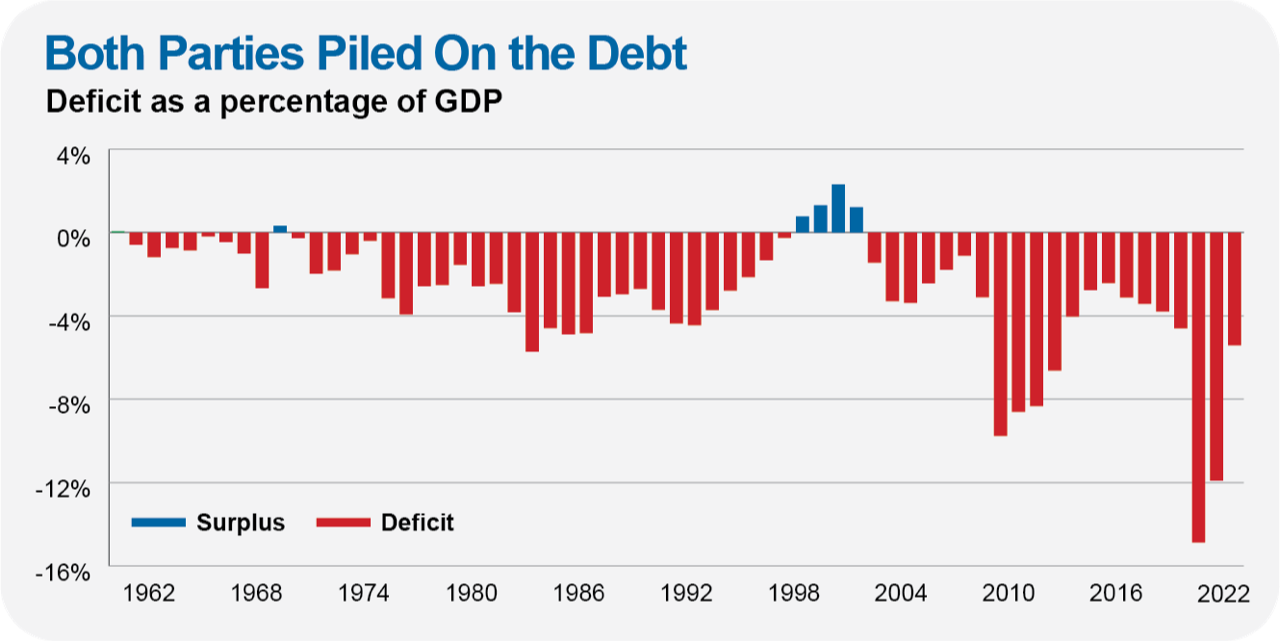

As you can see in the chart below, except for a few years around the turn of the century, our government has run a deficit (spent more than it took in) over the past 60-plus years. Tax cuts and increased spending have both contributed to the deficit over the years. And you can’t blame one political party or the other—they are both culpable.

So, where does the government get the money to fund its operations if tax receipts aren’t sufficient? The government makes up the difference between what it spends and what it collects in revenue by creating and selling Treasury bonds—borrowing money from investors like you and me, plus institutions around the world.

In our current system, Congress approves a budget—how much to spend. Then, long after the spending has been approved, Congress has a separate conversation about how to pay for it (by raising the debt ceiling and increasing borrowing, cutting programs, neither, or both).

Limiting our borrowing is logical—though as a nation we are still waiting to have an adult conversation about how much borrowing is too much. That’s the political and economic question.

But investors—including Warren Buffett (by his own admission)—have generally been too worried about deficits and the level of government debt over the years. We’ve done just fine.

Here’s Buffett talking about the deficit, stocks and gold in the context of the 77 years between his first investment (three shares of natural gas company Cities Service preferred stock that he purchased in 1942 at the age of 11) and the 2018 Berkshire annual report:

If my $114.75 had been invested in a no-fee S&P 500 index fund, and all dividends had been reinvested, my stake would have grown to be worth (pre-taxes) $606,811 on January 31, 2019 (the latest data available before the printing of this letter). That is a gain of 5,288 for 1. Meanwhile, a $1 million investment by a tax-free institution of that time – say, a pension fund or college endowment – would have grown to about $5.3 billion ...

Those who regularly preach doom because of government budget deficits (as I regularly did myself for many years) might note that our country’s national debt has increased roughly 400-fold during the last of my 77-year periods. That’s 40,000%! Suppose you had foreseen this increase and panicked at the prospect of runaway deficits and a worthless currency. To “protect” yourself, you might have eschewed stocks and opted instead to buy 31⁄4 ounces of gold with your $114.75.

And what would that supposed protection have delivered? You would now have an asset worth about $4,200, less than 1% of what would have been realized from a simple unmanaged investment in American business. The magical metal was no match for the American mettle.

I’m not arguing for unlimited borrowing, but the level of government debt has long been a reason bears have cited to avoid the markets—and one better ignored by investors.

Again, this isn’t a political newsletter. As investors, we need to deal with things as they are, not as we think they “should be.”

So here is where things stand, and how I think about them as a long-term investor.

Counting Down

The U.S. government hit the debt ceiling in January, and the U.S. Treasury has been using “extraordinary measures” to keep paying the bills. But it can only extend that game for so long.

Here is a look at the Treasury’s general account balance at the Federal Reserve (Fed). This is the primary operating account of the U.S. Treasury. Nearly all government disbursements are paid from here, while tax receipts go in.

In essence, this is the U.S. government’s checking account.